Extending HDP for Mutational Signatures: Incorporating Evolutionary Trees

In my previous blog post, I introduced the Hierarchical Dirichlet Process (HDP) as an elegant approach for mutational signature estimation. The HDP model allows us to simultaneously discover mutational signatures and estimate their activities across multiple samples while learning the number of signatures directly from the data.

However, the standard HDP approach treats each sample independently, missing a crucial biological insight: evolutionarily related cells should exhibit more similar mutational signature activities. In this follow-up post, I’ll present an extension of the HDP model that incorporates phylogenetic tree structures to capture this evolutionary relationship.

The Biological Motivation

With the advent of high-resolution techniques such as single-cell sequencing, we can now model the varying activities of mutational signatures within a tumor at unprecedented resolution. A key insight is that evolutionarily related cells should have more similar mutational signature activities than distantly related ones.

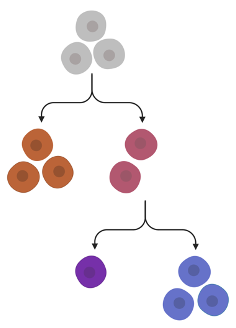

In cancer, a subclone represents a set of tumor cells descending from the same ancestor and hence sharing mutations. For many measurement modalities, there are established methods to infer relationships between subclones, often represented as tree structures. Examples include:

For our purposes, the specific tree construction method is less important than having a reliable tree topology. Depending on the type of mutational event under consideration and the available data, we can use any of these methods to infer relationships.

Consider the following example tree, where edges represent evolutionary relatedness:

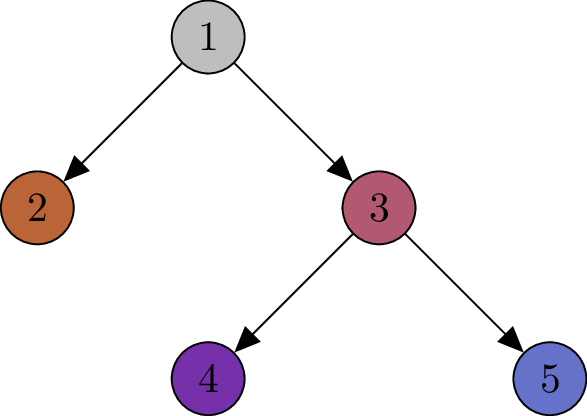

Note that we have varying numbers of cells per node. In particular, we can have 0 cells attached to a node of the tree. Let’s drop the number of cells per node and enumerate the nodes:

Let represent the topology of the tree. Without loss of generality, we assume a single tree for our input data. If multiple trees exist, such as when separate trees are constructed for different tumors, we can combine them by introducing a new root node and connecting the root nodes of the individual trees to this new root.

This tree consists of nodes . Each node can represent a subclone or serve as a connecting node. For each node we observe trinucleotide mutations . Note that is allowed. Let denote the activity catalogue in node .

The key biological insight: Subclones with closer evolutionary history should have more similar mutational signature activity. Let be a measure of dissimilarity on . In the above example we expect that . When we have access to tree topology , we can incorporate into our model as prior knowledge when inferring and consequently and .

The Tree-Structured HDP Model

Building on the standard HDP framework from my previous post, I now extend it to incorporate tree structure. The key modification is that instead of having all samples share a common base distribution , we now have a hierarchical structure where each node in the tree has its own Dirichlet Process that depends on its parent.

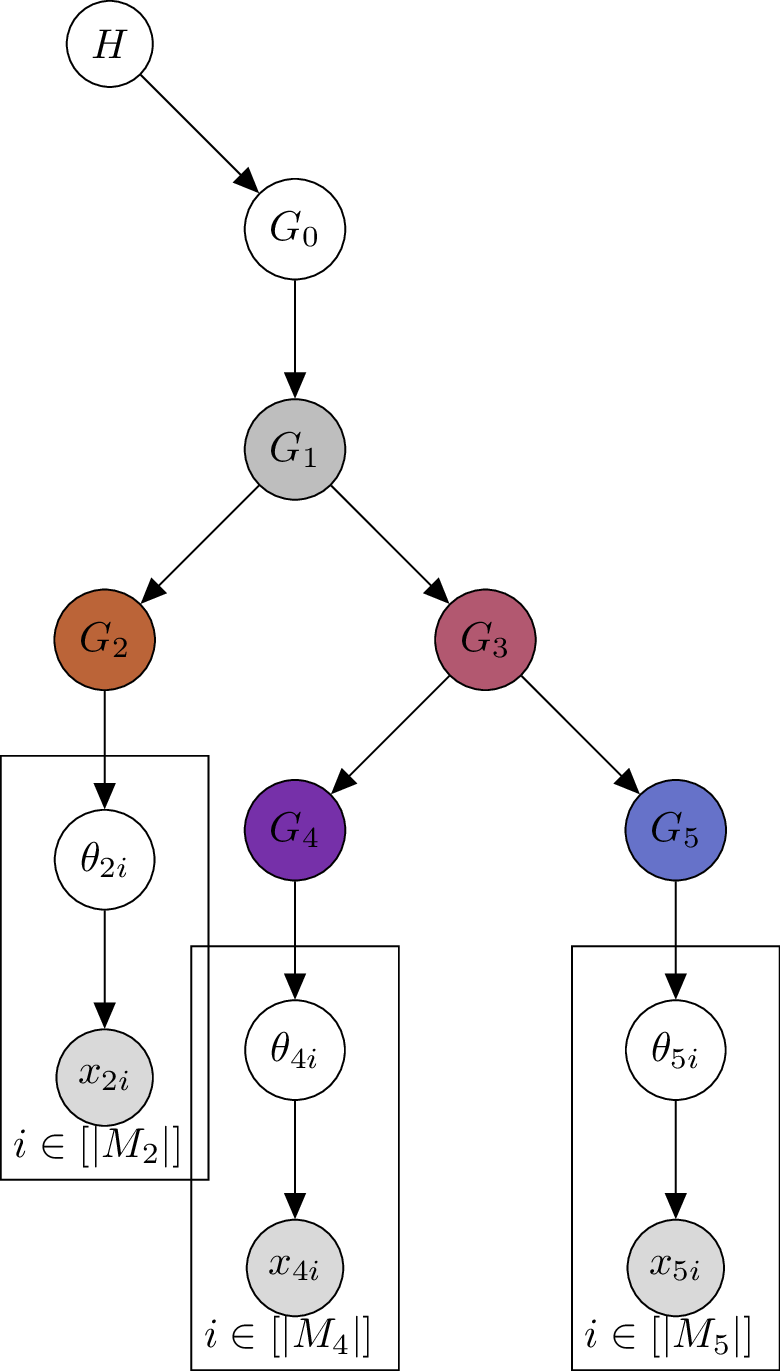

Sticking to the color coding from above, the graphical model of the proposed model looks as follows:

Each variable is a Dirichlet Process. For simplicity, we have omitted the scaling parameters for each Dirichlet process from the graph. In this example, we observe trinucleotide mutations in nodes but not in .

The key insight: Recall from the mathematical properties of the Dirichlet Process that and vary around . Similarly, and vary around . Hence, we can expect that the distribution of is more similar to than to . This means that should be more similar to than to , which directly addresses our biological motivation.

In the above example, is the base probability distribution of . Therefore, the support of is a subset of the support of , i.e., . A major shift in signature activity from node to could present a challenge for the model. It would be valuable to investigate whether such a shift is biologically plausible and, if so, to test the model in that scenario.

Mathematical Formulation

The sampling of , , and works exactly as in the classical HDP model from my previous post:

The key innovation is in the sampling of . Consider a tree topology . We write if and only if the -th node is a child of the -th node. Then we model the Dirichlet Process at each node of the tree as:

In words, at each node of the tree we draw from a Dirichlet Process with an individual scaling parameter and the base probability distribution from the parent node. By the mathematical properties of the Dirichlet Process, varies around the probability distribution of its parent node. Hence, distribution properties of get propagated to and further down the tree, ensuring that evolutionarily related nodes have similar mutational signature activities.

Challenges and Limitations

There are several challenges anticipated in making the proposed model practical. The first set of challenges relates to the input data requirements. To construct a tree of relatedness, we need sequencing at a subtumor level, such as sequencing at single-cell or subclonal level. The tumor sample must contain a sufficient number of trinucleotide mutations, typically seen in late-stage tumors. To be able to measure a sufficient number of the trinucleotide mutations, sequencing must cover a large enough genomic region.

Next Steps and Future Directions

Implementation

The current implemented prototype is a fork of the HDP implementation by Nicola Roberts in R with some helper functions. As a next step, an implementation of the package in Python would be interesting to make it more accessible to the broader community.

Benchmarking Against Standard Methods

A crucial next step is to benchmark the tree-structured HDP against standard approaches. The evaluation strategy would involve:

- Dataset Selection: Choose a dataset suitable for the proposed method with available tree topology

- Method Comparison: Estimate mutational signatures using:

- Classical NMF approach: and

- Tree-structured HDP: and

- Evaluation: Compare how well the estimated signature activities and respect the known tree topology

Alternative Approaches

Instead of the Hierarchical Dirichlet Process approach, we could utilize variations of Non-negative Matrix Factorization. Given observed mutation catalogue and a constructed tree topology , we could introduce a penalization term to ensure that the tree topology is respected:

A desirable property of the function would be that for samples attached to nodes in the graph which are close to each other, we have similar and .

Alternatively, we could explore hierarchical NMF approaches. There is abundant literature on NMF and its variations, including Sugahara et al., Ding et al., Ferreira et al., and Schmidt & Raphael.

Extension to Other Mutational Events

Instead of focusing solely on trinucleotide mutational events, we could study other mutational events with the proposed model. For example, we could study chromosomal instability events using the approach described in Drews et al.. However, this would introduce additional requirements to the input data, such as high read depth, and such datasets are not yet widely available.

Recommended material for chromosomal instability events

- https://markowetz.cruk.cam.ac.uk/cincompendium/

- https://github.com/markowetzlab/CINSignatureQuantification

- calculateFeatures function

- R package to quantify signatures of chromosomal instability on absolute copy number profiles as described in Drews et al.

Comparison with Existing Literature

It would be beneficial to explore how the proposed approach compares to existing literature, such as Alam et al., to understand the theoretical and practical advantages of our tree-structured approach.

Conclusion

This follow-up post has presented an extension of the standard HDP model for mutational signature estimation that incorporates evolutionary tree structure. By leveraging the biological insight that evolutionarily related cells should have more similar mutational signature activities, the tree-structured HDP model provides a principled way to incorporate phylogenetic information into mutational signature analysis.

The key innovation lies in the hierarchical structure where each node in the tree has its own Dirichlet Process that depends on its parent, ensuring that distribution properties propagate down the tree. This addresses a fundamental limitation of standard approaches that treat samples independently.

While there are practical challenges related to data requirements and implementation, the theoretical framework provides a solid foundation for future work in this area. The next steps involve implementation, benchmarking, and exploring alternative approaches to validate and improve upon this initial proposal.